Formation of INEQUALITY

Inequality through History

Power, Structure, History, Human Consequence and Colonial Legacies

MLA Educational Series

Written and Researched by James Vegter

Magic Lands Alliance – Advanced Research

2026

ABSTRACT

Inequality is not merely the uneven distribution of wealth. It is a multidimensional structure shaping access to power, land, opportunity, education, health, and recognition. Across history, inequality has been justified through cosmology, religion, race, class, gender, and economics. Modern societies often frame inequality as inevitable or meritocratic; however, philosophical, economic, and anthropological scholarship reveals inequality as structurally produced and historically contingent.

This doctoral manuscript develops an interdisciplinary analysis of inequality across deep history, classical philosophy, Enlightenment liberalism, Marxist critique, colonial expansion, Indigenous dispossession, industrial capitalism, neoliberal globalisation, and contemporary digital economies. It integrates psychological research on status and hierarchy, sociological theory on stratification, and contemporary debates on justice (Rawls 1971; Sen 1999; Piketty 2014).

The central thesis argues that inequality is not an accidental by-product of civilisation but a system of organised advantage rooted in power consolidation. Sustainable futures require reconfiguring inequality from extractive hierarchy toward relational equity.

DEFINING INEQUALITY

Inequality refers to structured differences in access to resources, rights, recognition, and power. It manifests across multiple domains:

· Economic inequality (income, wealth distribution)

· Political inequality (representation, governance access)

· Racial and ethnic inequality

· Gender inequality

· Colonial inequality

· Educational inequality

· Health inequality

· Digital inequality

While differences between individuals are natural, structural inequality emerges when differences become institutionalised and self-reinforcing.

Modern economic inequality is often measured through the Gini coefficient or wealth concentration ratios. Yet inequality is not merely statistical. It is lived experience.

DEEP HISTORY — HIERARCHY AND EARLY SOCIETIES

Hunter-Gatherer Egalitarianism

Anthropological evidence suggests many hunter-gatherer societies were relatively egalitarian. Mobility limited accumulation. Leadership was situational rather than hereditary (Boehm 1999). Social cohesion required sharing.

Inequality increases with sedentism.

Agricultural Surplus and Stratification

The Neolithic Revolution (c. 10,000 BCE) enabled surplus production. Surplus enabled storage. Storage enabled control. Control enabled hierarchy.

With agriculture emerged:

· Property ownership

· Inheritance systems

· Class differentiation

· Patriarchal consolidation

Archaeological evidence shows increasing wealth stratification in early urban centres such as Mesopotamia and Egypt.

Inequality became institutional.

GREEK AND CLASSICAL PHILOSOPHY OF HIERARCHY

Greek philosophy both critiqued and justified inequality.

Plato and Hierarchical Order

In The Republic, Plato proposed a stratified society of rulers, guardians, and producers. Hierarchy was justified through natural aptitude. Justice meant each class performing its role.

Inequality was naturalised.

Aristotle and Natural Slavery

Aristotle argued some individuals were “natural slaves,” lacking rational capacity for self-governance. This provided philosophical grounding for hierarchical social order.

Greek democracy coexisted with slavery.

Inequality was embedded in classical political theory.

RELIGION AND DIVINE ORDER

Medieval European societies justified inequality through divine hierarchy. The “Great Chain of Being” positioned monarchs near divinity and peasants near base existence. Social rank reflected divine will.

Similarly, caste systems in South Asia structured hereditary inequality over millennia (Dirks 2001).

Religious cosmology legitimised stratification.

ENLIGHTENMENT AND LIBERAL EQUALITY

The Enlightenment introduced a radical shift. Thinkers such as John Locke argued for natural rights. Rousseau (1755) critiqued private property as origin of inequality. The American and French Revolutions proclaimed equality before the law.

Yet liberal equality focused on legal equality, not economic equality.

Slavery persisted.

Colonial expansion intensified.

COLONIALISM AND STRUCTURAL INEQUALITY

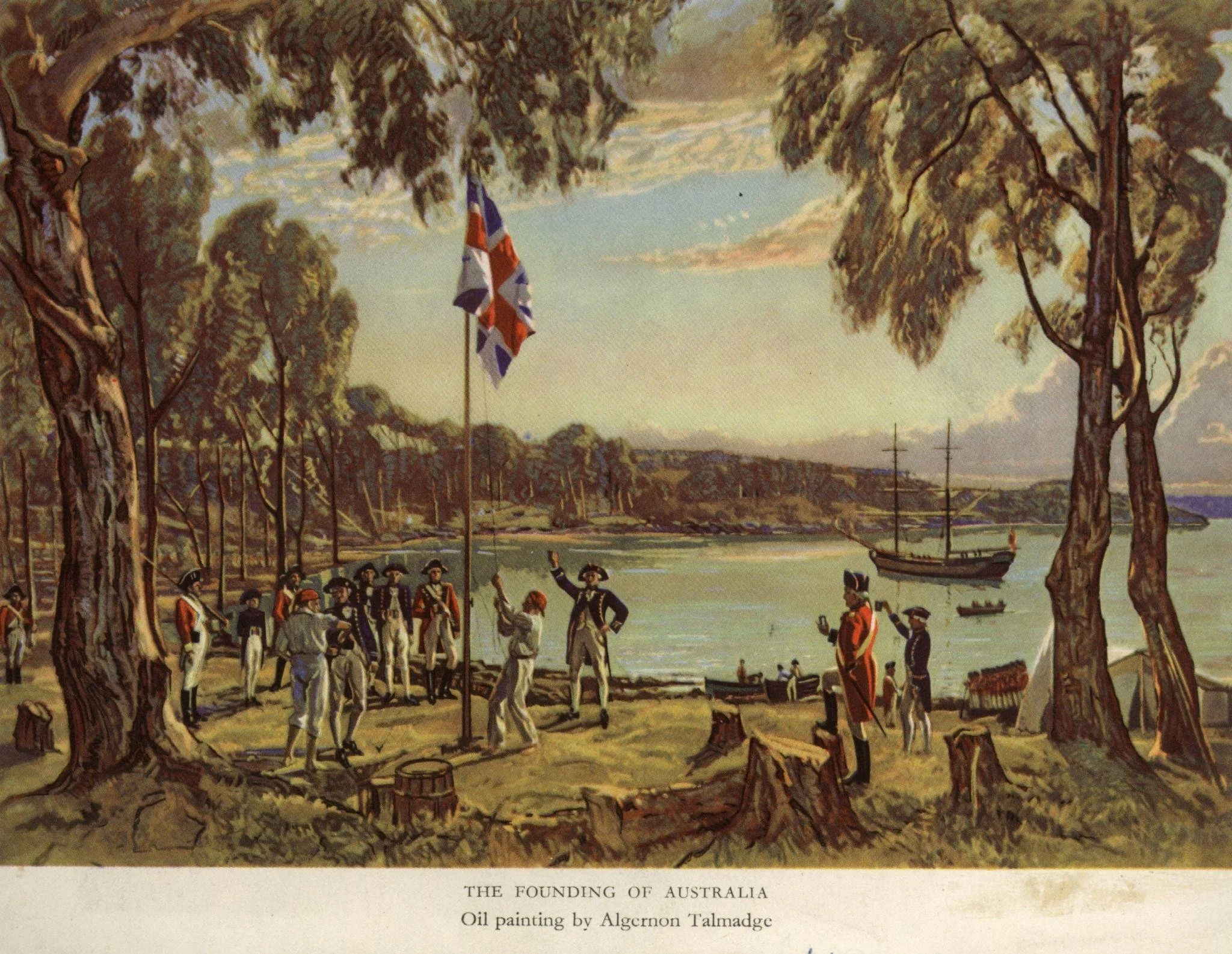

European colonial expansion from the fifteenth century onward created global inequality structures. Land dispossession, resource extraction, and racial classification consolidated power.

In Australia, British colonisation dispossessed Indigenous peoples of land, sovereignty, and economic base. Terra nullius doctrine erased Indigenous governance systems. Economic inequality was structurally embedded through land seizure and labour exclusion (Reynolds 1987).

Colonial inequality persists intergenerationally.

MARX AND STRUCTURAL ECONOMIC INEQUALITY

Karl Marx reframed inequality as structural exploitation embedded in capitalism. In Capital (1867), Marx argued that surplus value extraction from labour generates class stratification. Capital accumulates in fewer hands.

Inequality is systemic, not accidental.

Modern data supports concentration trends. Piketty (2014) demonstrates that when return on capital exceeds economic growth (r > g), wealth concentrates.

Inequality compounds.

LIBERAL JUSTICE, FAIRNESS, AND THE LIMITS OF FORMAL EQUALITY

The twentieth century witnessed renewed philosophical engagement with inequality through liberal political theory. John Rawls’ A Theory of Justice (1971) sought to reconcile freedom with fairness. Rawls proposed that principles of justice should be chosen behind a “veil of ignorance,” where individuals do not know their social position, wealth, or talents. In such a hypothetical condition, rational actors would design institutions that protect basic liberties and ensure that inequalities benefit the least advantaged. This latter condition, known as the Difference Principle, permits inequality only when it improves the situation of those at the bottom.

Rawls’ framework represented a moral advance over laissez-faire liberalism. However, critics argue that Rawls presumes stable institutional conditions and underestimates structural power. Formal equality under law does not dismantle historical disadvantage. If individuals begin from radically unequal starting positions, procedural fairness may preserve inequality rather than resolve it.

Amartya Sen (1999) extended the debate by shifting attention from resources to capabilities. For Sen, inequality should be assessed in terms of what individuals are actually able to do and be. Income equality alone is insufficient if health, education, or social recognition remain constrained. The capability approach reveals inequality as multidimensional rather than purely economic.

Together, Rawls and Sen demonstrate that justice cannot be reduced to market outcomes. Institutions structure life chances.

GENDER INEQUALITY AND STRUCTURAL PATRIARCHY

Gender inequality is among the most persistent forms of stratification. Historically, patriarchal systems concentrated property ownership, political authority, and inheritance rights in male hands. Women were excluded from formal political participation across most societies until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Simone de Beauvoir (1949) argued that woman has historically been constructed as “Other,” socially defined in relation to male normativity. Gender inequality is not merely economic disparity; it is structural subordination embedded in culture, labour division, and representation.

Contemporary gender inequality persists through wage gaps, unpaid care labour, underrepresentation in political leadership, and exposure to violence. Structural inequality reproduces itself across generations through norms, education, and economic systems.

Gender inequality intersects with race and class, producing compounded disadvantage.

RACIAL INEQUALITY AND COLONIAL LEGACIES

Racial inequality emerged as a justificatory system during European colonial expansion. Scientific racism, slavery, and legal segregation institutionalised hierarchical classifications. In settler-colonial contexts such as Australia, Indigenous peoples were dispossessed of land, governance, and economic base (Reynolds 1987).

Land dispossession produces enduring inequality. Economic capital, once extracted, compounds across generations. Meanwhile, communities excluded from property ownership face structural barriers to accumulation.

In contemporary societies, racial inequality manifests in disparities in incarceration rates, educational attainment, health outcomes, and income distribution. Structural racism operates through institutional design rather than solely through overt prejudice.

Inequality becomes embedded in systems.

PSYCHOLOGICAL AND BIOLOGICAL CONSEQUENCES OF INEQUALITY

Inequality is not merely material; it has psychological and physiological consequences. Wilkinson and Pickett (2009) argue that more unequal societies exhibit higher rates of mental illness, violence, and reduced social trust. Relative deprivation—the perception of lower status compared to others—activates stress responses.

Neuroscientific research demonstrates that chronic stress associated with socioeconomic insecurity affects cognitive development and long-term health. Cortisol dysregulation and allostatic load correlate with persistent inequality exposure.

Inequality shapes bodies as well as institutions.

Children raised in poverty experience reduced educational opportunity not only because of resource scarcity but because stress environments impair cognitive bandwidth. Inequality thus becomes biologically embodied.

EDUCATION, MOBILITY, AND INTERGENERATIONAL STRATIFICATION

Education is often framed as the pathway to mobility. Yet educational systems frequently reproduce inequality. Access to quality schooling correlates strongly with neighbourhood wealth. Elite institutions perpetuate social networks that reinforce advantage.

Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital (1986) explains how non-economic assets—language style, behavioural norms, institutional familiarity—reinforce stratification. Meritocracy often disguises inherited advantage.

Intergenerational wealth transmission intensifies inequality. Piketty (2014) demonstrates that when returns on capital exceed economic growth, wealth concentration accelerates. Inherited capital reproduces itself faster than wages can compete.

Inequality compounds across time.

GLOBAL INEQUALITY AND NEOLIBERAL GLOBALISATION

Global inequality reflects centuries of colonial extraction and contemporary trade imbalances. Wealth accumulation in industrialised nations often correlates with historical resource extraction from colonised regions.

Neoliberal globalisation since the late twentieth century intensified capital mobility while labour remained geographically constrained. Corporations leverage global supply chains to minimise labour costs. Wealth concentrates in financial centres.

While global poverty rates have declined in absolute terms, wealth concentration at the top has increased dramatically (Piketty 2014). The top percentile accumulates disproportionate capital.

Inequality is globalised.

DIGITAL AND ALGORITHMIC INEQUALITY

The digital age introduces new stratifications. Access to high-speed internet, digital literacy, and algorithmic influence shapes opportunity. Technology platforms consolidate data ownership and market dominance.

Algorithmic systems may reproduce bias embedded in historical data. Credit scoring, predictive policing, and hiring algorithms can reinforce structural inequality.

Digital capitalism amplifies asymmetry between platform owners and users.

CLIMATE CHANGE AND THE ANTHROPOCENE

Climate inequality represents one of the defining justice challenges of the twenty-first century. Those least responsible for greenhouse emissions—often low-income and Indigenous communities—experience disproportionate environmental impacts.

The Anthropocene collapses temporal scales. Industrial activity within two centuries alters geological systems shaped over millennia. Climate change exposes the asymmetry between economic power and ecological vulnerability.

Future generations inherit environmental debt.

Inequality now operates across time.

STRUCTURAL VS RELATIONAL MODELS OF INEQUALITY

Traditional inequality analysis focuses on distribution—who has how much. A deeper structural analysis examines how institutions produce and reproduce disparity. Land ownership, taxation policy, educational access, corporate governance, and political representation form systemic architecture.

Relational models emphasise interdependence rather than competition. Indigenous governance systems often prioritised reciprocity and communal responsibility rather than accumulation.

Inequality is not inevitable. It is structured.

Structures can change.

TOWARD RELATIONAL EQUITY

Relational equity shifts the focus from accumulation to balance. It recognises:

· Historical context

· Intergenerational transmission

· Ecological limits

· Community interdependence

Policy responses may include progressive taxation, land restitution, educational reform, universal healthcare, and democratic participation expansion. However, structural reform requires cultural transformation.

The ideology of scarcity must give way to frameworks of shared flourishing.

AUSTRALIAN INEQUALITY — STRUCTURE, HISTORY, AND CONTEMPORARY DISPARITIES

Australia presents a distinctive case study in inequality because it combines advanced liberal democracy, high per-capita wealth, and persistent structural disparities rooted in colonial dispossession and economic concentration. While Australia ranks highly on global human development indices, wealth distribution, land ownership, incarceration, housing access, and intergenerational mobility reveal entrenched inequality patterns.

Colonial Foundations of Structural Inequality

British colonisation of Australia in 1788 was legally justified through the doctrine of terra nullius, which declared the continent legally uninhabited despite tens of thousands of years of Indigenous occupation. This legal fiction erased Indigenous sovereignty and enabled wholesale land appropriation (Reynolds 1987). Land in settler-colonial societies functions not merely as territory but as economic infrastructure. Its seizure transferred agricultural, mineral, and commercial opportunity into colonial hands.

The dispossession of land severed Indigenous communities from economic base, governance systems, and food security. Unlike many post-colonial states where independence movements reclaimed political sovereignty, Australia remains a settler-colonial nation-state in which the descendants of colonisers retain dominant land tenure and capital concentration.

The legal reversal of terra nullius in the High Court’s Mabo (No 2) decision (1992) acknowledged pre-existing Indigenous law and land rights. However, recognition did not equate to restitution. Native title claims are limited to land not already extinguished by freehold or exclusive tenure. Given that the most economically productive land had already been alienated, native title recognition has been partial and uneven.

Thus, inequality in Australia is not accidental. It is structurally rooted in foundational land transfer.

Wealth Concentration and Housing Inequality

Australia’s modern inequality is increasingly shaped by housing markets and capital gains structures. Over the past four decades, housing has become the primary vehicle for wealth accumulation. Policies such as negative gearing and capital gains tax concessions disproportionately benefit property owners.

Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS 2022) shows that the top 20% of households hold approximately 60% of total wealth, while the bottom 20% hold less than 1%. Intergenerational wealth transfer increasingly determines housing access. Younger Australians face declining home ownership rates compared to previous generations at similar ages.

This transformation shifts inequality from income-based to asset-based stratification. When capital appreciation outpaces wage growth—echoing Piketty’s (2014) global thesis that r > g—wealth consolidates structurally.

Housing inequality also produces spatial inequality. Socio-economic segregation shapes educational access, healthcare proximity, and employment opportunity. Geographic postcode becomes predictor of life trajectory.

Indigenous Incarceration and Justice Inequality

One of the most visible expressions of inequality in Australia is incarceration disparity. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples comprise approximately 3–4% of the population yet represent over 30% of the national prison population (ABS 2023). This overrepresentation cannot be understood outside the context of socio-economic marginalisation, policing practices, and historical dispossession.

The 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody identified structural disadvantage as central driver. Subsequent decades have seen limited reduction in disparity. Incarceration perpetuates economic exclusion, employment barriers, and community disruption.

Justice inequality is cumulative. It compounds historical disadvantage into present marginalisation.

Education, Health, and Intergenerational Disadvantage

Educational outcomes correlate strongly with socio-economic background. Remote Indigenous communities face reduced access to secondary schooling and tertiary pathways. Health disparities remain pronounced, with lower life expectancy and higher rates of chronic illness among Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2022).

Intergenerational inequality emerges where poverty, reduced schooling access, and housing instability intersect. Inequality is not episodic; it is transmitted.

The Closing the Gap framework, established to address these disparities, has achieved limited success in structural transformation. Targets frequently focus on outcomes without fully addressing land, economic autonomy, and governance structures.

INDIGENOUS LAND RIGHTS — LAW, ECONOMY, AND RESTORATIVE JUSTICE

Mabo and the Legal Recognition of Native Title

The 1992 High Court decision in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) overturned the doctrine of terra nullius and recognised that Indigenous land rights survived colonisation where not extinguished. The subsequent Native Title Act 1993 established procedures for land claims.

However, native title is legally fragile. It can be extinguished by prior freehold grants, infrastructure development, or inconsistent tenure. Recognition does not automatically confer economic capacity.

The distinction between land rights (as seen in the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1976 in the Northern Territory) and native title is critical. Land rights legislation can provide stronger tenure and economic autonomy. Native title recognition is often symbolic unless accompanied by negotiated economic agreements.

Land as Economic Foundation

Land is not only cultural identity; it is capital. Dispossession removed access to agricultural production, mineral royalties, fisheries, and ecological management. Contemporary land settlements increasingly incorporate economic dimensions, including negotiated mining agreements and joint management of national parks.

Yet cases such as the destruction of Juukan Gorge in 2020 demonstrate the vulnerability of heritage protections within extractive economies. Legal recognition without structural economic power remains insufficient.

True land justice requires economic restitution, not solely symbolic recognition.

The Uluru Statement and Constitutional Reform

The 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart called for a constitutionally enshrined Voice to Parliament, treaty processes, and truth-telling. The 2023 referendum on the Voice was unsuccessful. Nevertheless, the movement reflects ongoing negotiation over political equality and representation.

Structural inequality persists where governance frameworks exclude those most affected by policy.

Political voice is a dimension of equality.

Yoorrook Justice Commission and Truth-Telling

The Yoorrook Justice Commission in Victoria represents the first formal truth-telling process into historical injustices against First Peoples. Truth processes reveal how land dispossession, violence, and exclusion produced structural disadvantage.

Recognition without redistribution risks perpetuating inequality.

Truth is precondition for structural reform.

Toward Relational Land Justice

A relational approach to land justice integrates:

· Legal recognition

· Economic participation

· Cultural continuity

· Environmental stewardship

· Shared governance

Indigenous land management practices offer sustainable ecological frameworks relevant to climate adaptation. Land rights thus intersect with environmental justice and intergenerational equity.

Inequality rooted in land requires land-based restoration.

INEQUALITY ACROSS TIME — INTERGENERATIONAL AND CLIMATE DIMENSIONS

Inequality operates not only across populations but across generations. Wealth inheritance structures opportunity before birth. Climate change introduces temporal injustice: those least responsible bear disproportionate consequences.

Future generations inherit ecological debt and economic imbalance.

Intergenerational justice extends inequality analysis beyond present distribution into temporal responsibility.

PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACT OF INEQUALITY

Inequality is not experienced solely as material deprivation; it is lived psychologically. Beyond income gaps and asset concentration, inequality structures perception, identity, stress physiology, social trust, and cognitive development. The psychological consequences of inequality operate through both absolute deprivation and relative status comparison.

Relative Deprivation and Status Anxiety

Human beings are deeply attuned to social hierarchy. Wilkinson and Pickett (2009) argue that in highly unequal societies, social comparison intensifies. Individuals evaluate themselves relative to others, producing status anxiety, diminished self-worth, and chronic stress. The psychological burden of inequality is therefore relational, not merely economic.

Relative deprivation theory suggests that individuals experience distress not simply because they lack resources, but because they perceive unfair disadvantage compared to others. In societies where wealth disparities are highly visible, perceived injustice intensifies psychological strain.

Inequality thus shapes emotional climate.

Chronic Stress and Allostatic Load

Persistent socio-economic insecurity activates chronic stress responses. The body’s stress system—particularly the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis—releases cortisol in response to threat. When exposure is prolonged, stress becomes biologically embedded.

Research in social epidemiology demonstrates that individuals in lower socio-economic positions exhibit higher allostatic load—cumulative biological wear and tear resulting from chronic stress exposure (Marmot 2004). This contributes to increased rates of cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders, and reduced life expectancy.

Inequality therefore manifests physiologically.

Cognitive Bandwidth and Decision-Making Under Scarcity

Scarcity affects cognition. Behavioural research suggests that financial precarity reduces cognitive bandwidth, narrowing attentional focus and impairing long-term planning (Mullainathan & Shafir 2013). Decision-making under scarcity becomes reactive rather than strategic.

In this sense, inequality constrains agency not only materially but cognitively. Poverty becomes self-reinforcing when stress impairs executive function.

Early Childhood Development

Inequality exerts disproportionate impact during early childhood. Neural development is highly sensitive to environmental conditions. Chronic stress exposure in early life alters neural circuitry associated with emotional regulation and executive control.

Socio-economic gradients correlate strongly with educational attainment and later employment outcomes. Inequality becomes intergenerational through developmental pathways.

Social Trust and Collective Cohesion

Highly unequal societies demonstrate lower levels of interpersonal trust (Wilkinson & Pickett 2009). Trust is foundational to democratic stability, civic engagement, and cooperative institutions. When inequality widens, social fragmentation increases.

Psychologically, inequality produces isolation.

SCIENTIFIC DIMENSIONS OF INEQUALITY

Inequality is not solely a moral or political issue. It has measurable scientific dimensions across biology, neuroscience, epidemiology, systems theory, and environmental science. Examining inequality through scientific frameworks reveals its systemic character.

Biological Embedding and Epigenetics

Emerging research in epigenetics suggests that chronic stress associated with socio-economic disadvantage can alter gene expression. Environmental stressors influence biological systems, potentially affecting health outcomes across generations.

This phenomenon, sometimes referred to as “biological embedding,” demonstrates how inequality becomes physically inscribed into bodies.

Inequality is not abstract. It becomes cellular.

Epidemiology and the Social Gradient

The “social gradient in health,” articulated by Marmot (2004), demonstrates that health outcomes improve incrementally at each higher socio-economic tier. The relationship is not binary (poor vs rich) but continuous.

This gradient indicates that inequality affects entire populations, not only those at the bottom. More unequal societies exhibit worse aggregate health outcomes, even among the relatively affluent.

Scientific evidence thus undermines the notion that inequality harms only the disadvantaged.

Neuroscience of Status Hierarchies

Neuroscientific studies reveal that social status affects neural reward systems. Hierarchical positioning activates dopaminergic pathways associated with reward and stress responses. Low-status positioning correlates with increased amygdala activation, associated with threat processing.

Status is biologically processed.

Inequality therefore influences neurological states.

Environmental and Climate Science

Climate inequality demonstrates how environmental systems intersect with social stratification. Lower-income communities often experience greater exposure to pollution, extreme heat, and climate vulnerability.

Environmental justice research reveals that industrial zoning, infrastructure placement, and resource extraction disproportionately affect marginalised communities.

Inequality shapes environmental risk distribution.

Systems Theory and Feedback Loops

From a systems perspective, inequality operates through reinforcing feedback loops. Wealth accumulation enables investment, which generates further capital gains. Conversely, deprivation limits opportunity, reducing mobility and perpetuating disadvantage.

Systems theory reveals inequality as dynamic rather than static. It self-reinforces unless interrupted through structural intervention.

INTEGRATED SYNTHESIS: INEQUALITY AS PSYCHO-SOCIAL SYSTEM

The psychological and scientific dimensions of inequality reveal its depth. Inequality is:

· Economically structured

· Historically rooted

· Psychologically embodied

· Biologically embedded

· Environmentally distributed

· Systemically reinforced

It operates across individual experience and macro-structures simultaneously.

Understanding inequality therefore requires interdisciplinary analysis.

Justice must be structural because inequality is systemic.

CONCLUSION

Inequality is neither accidental nor merely statistical. It is structured power operating across history, institutions, bodies, and generations. From the consolidation of agricultural surplus in early stratified societies to colonial land dispossession in Australia; from industrial capitalism to contemporary asset speculation and digital monopolies; from legal doctrines such as terra nullius to modern incarceration systems—inequality has been repeatedly institutionalised, normalised, and reproduced.

The Australian case demonstrates this with particular clarity. Indigenous land dispossession represents the foundational axis of structural inequality. Land transfer was not merely territorial expansion; it was economic displacement. Land functions as capital, governance base, cultural continuity, and ecological infrastructure. Without land, economic autonomy collapses. Without political inclusion, structural disadvantage persists. Legal recognition without economic restitution remains incomplete justice.

Across intellectual traditions, inequality has been alternately justified and critiqued. Aristotle naturalised hierarchy. Medieval cosmologies sanctified rank. Enlightenment liberalism proclaimed equality before the law while tolerating material disparity. Marx exposed structural exploitation embedded in capital accumulation. Rawls reframed justice through fairness, and Sen expanded evaluation toward capabilities rather than income alone. These debates reveal that inequality is not fate—it is institutional design.

Economic research demonstrates how wealth concentrates when returns on capital outpace economic growth (Piketty 2014). Sociological analysis reveals how cultural capital reproduces advantage across generations (Bourdieu 1986). Psychological research demonstrates that inequality is biologically embodied through chronic stress and social fragmentation (Wilkinson & Pickett 2009; Marmot 2004). Climate science introduces an intergenerational dimension: those least responsible for ecological degradation bear disproportionate consequences.

Inequality is therefore multidimensional: economic, political, racial, gendered, psychological, ecological, and temporal. It shapes who accumulates and who is excluded, who inherits and who is dispossessed, who participates in governance and who remains marginalised.

If time structures existence, inequality structures opportunity within that time.

The decisive question is not whether inequality exists; hierarchy has emerged in nearly every complex society. The question is whether societies choose to perpetuate extractive systems of organised advantage or to redesign institutions toward relational equity.

A sustainable and just future requires structural transformation—land justice, economic redesign, democratic inclusion, educational access, health equity, and ecological responsibility. Inequality is not natural hierarchy; it is organised advantage sustained through systems.

Justice, therefore, requires organised redesign.

REFERENCE LIST

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2022, Household Wealth and Wealth Distribution, Australia, ABS, Canberra.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2023, Prisoners in Australia, ABS, Canberra.

Aristotle 350 BCE, Politics.

Boehm, C 1999, Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Bourdieu, P 1986, ‘The Forms of Capital’, in J Richardson (ed.), Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, Greenwood Press, New York, pp. 241–258.

de Beauvoir, S 1949, The Second Sex, Gallimard, Paris.

Dirks, N 2001, Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the Making of Modern India, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Marx, K 1867, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol. 1, Otto Meissner Verlag, Hamburg.

Marmot, M 2004, The Status Syndrome: How Social Standing Affects Our Health and Longevity, Bloomsbury, London.

Mullainathan, S & Shafir, E 2013, Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much, Times Books, New York.

Piketty, T 2014, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Rawls, J 1971, A Theory of Justice, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Reynolds, H 1987, The Law of the Land, Penguin, Melbourne.

Rousseau, JJ 1755, Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men.

Sen, A 1999, Development as Freedom, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Wilkinson, R & Pickett, K 2009, The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better, Allen Lane, London.

Yoorrook Justice Commission 2023, Interim Report, Yoorrook Justice Commission, Melbourne.

Written and Researched by James Vegter (17th, February, 2026)

MLA

Sharing the truth of Indigenous and colonial history through film, education, land, and community.

www.magiclandsalliance.org

Copyright MLA – 2025

Magic Lands Alliance acknowledges the Traditional Owners, Custodians, and First Nations communities across Australia and internationally. We honour their enduring connection to the sky, land, waters, language, and culture. We pay respect to Elders past, present, and emerging, and to all First Peoples’ communities and language groups. This article draws only on publicly available information; many cultural practices remain the intellectual property of their respective communities.

A DEEP DIVE into TIME

History of Time

Cosmology, Country, Deep History, and Human Consciousness

MLA Educational Article

Written and Researched by James Vegter

Magic Lands Alliance

2026

ABSTRACT

Time is among the most foundational yet contested concepts in human thought. It operates across multiple scales: cosmological, geological, biological, cultural, psychological, and existential. Western industrial modernity has largely reduced time to a measurable, linear, economic resource, yet global philosophical traditions reveal alternative temporal ontologies—cyclical, relational, ancestral, ecological, and phenomenological. This manuscript develops an interdisciplinary philosophy of time integrating cosmology (Big Bang and entropy), deep human origins in Africa (~300,000 years), Indigenous Australian temporal systems (including Wadawurrung astronomy and the Budj Bim cultural landscape), African cosmologies (San, Yoruba, Dogon, Nilotic), Greek metaphysics, Daoist flow, Buddhist impermanence, phenomenology (Bergson, Heidegger, Husserl), psychological time perception, ageing theory, and contemporary sociological acceleration theory.

The central thesis argues that time is not merely a neutral metric but a structuring worldview that shapes identity, governance, ecology, and consciousness. Modern acceleration fragments time; relational frameworks restore continuity. By situating human existence within deep cosmological and ancestral time, this manuscript proposes a reframing of temporal consciousness suitable for the Anthropocene.

THE PROBLEM OF TIME

Few concepts are as familiar and yet as elusive as time. We live within it, measure it, fear its passing, and structure entire civilisations around its calculation. Yet when pressed to define it, clarity dissolves. Augustine famously confessed: “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I wish to explain it, I do not know” (Augustine 397 CE).

The problem of time is not singular. It manifests differently depending on scale:

· At the cosmological level, time begins with the Big Bang.

· At the geological level, time is measured in millions of years.

· At the evolutionary level, time structures species emergence.

· At the cultural level, time organises memory and ritual.

· At the psychological level, time stretches and compresses.

· At the existential level, time defines mortality.

Western modernity has privileged quantitative, linear temporality. Time becomes divisible, synchronised, commodified. The industrial revolution mechanised temporal order (Landes 1983). Railway timetables and time zones abstracted time from place. Productivity metrics transformed duration into economic value. Benjamin Franklin’s maxim “Time is money” encapsulates this reduction.

Yet this linear abstraction is historically recent.

Indigenous cultures across the globe maintain relational temporal frameworks embedded in ecology and ancestry (Stanner 1956; Lee 1979). Greek philosophy wrestled with flux and permanence. Daoism emphasised rhythmic harmony. Buddhism denied enduring permanence altogether.

This manuscript asks: What is time when examined across all scales simultaneously?

COSMOLOGICAL TIME — THE BEGINNING OF TIME

The Big Bang and the Emergence of Spacetime

Modern cosmology situates the origin of time approximately 13.8 billion years ago. Observations from the Planck satellite confirm that the universe expanded from an extremely dense and hot early state (Planck Collaboration 2020). Crucially, the Big Bang does not describe an explosion within pre-existing space. Rather, it marks the origin of spacetime itself.

General relativity (Einstein 1916) describes spacetime as dynamic, curved by mass and energy. When extrapolated backward, cosmic expansion leads to an initial state beyond which classical equations fail. Hawking (1988) argued that asking what occurred “before” the Big Bang may be meaningless because time itself began at that boundary.

This radically alters metaphysical assumptions. Time is not eternal background. It is emergent.

Evidence for Cosmological Time

Three pillars support the Big Bang model:

First, cosmic microwave background radiation (Penzias & Wilson 1965) provides thermal afterglow evidence of an early hot universe. Second, galactic redshift observations reveal universal expansion. Third, primordial element abundances align with early nucleosynthesis predictions.

Together, these demonstrate that time has cosmological direction.

Entropy and the Arrow of Time

Physical laws at the micro level are largely time-symmetric. Yet macroscopic experience is not. Eggs break but do not reassemble. We remember the past, not the future.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics explains this asymmetry: entropy increases in closed systems. Rovelli (2018) argues that the arrow of time emerges from entropy gradients. The early universe existed in a remarkably low-entropy state. Its subsequent evolution generates irreversibility.

Time flows because entropy increases.

Cosmological time therefore has:

· A beginning (Big Bang)

· A direction (entropy)

· A relational structure (spacetime curvature)

Time at this scale dwarfs human history.

GEOLOGICAL TIME — EARTH AND MEMORY

Deep Earth Time

Earth formed approximately 4.5 billion years ago. Geological strata record vast epochs beyond human comprehension. Yet within this deep scale, cultural memory can persist.

Budj Bim: Convergence of Science and Story

Budj Bim, on Gunditjmara Country in western Victoria, erupted approximately 36,900 years ago (Matchan et al. 2020). Oral traditions recount ancestral volcanic transformation. Geological dating confirms late Pleistocene eruption.

The Budj Bim Cultural Landscape includes one of the world’s oldest aquaculture systems, extending over at least 6,000 years (UNESCO 2019). Stone channels and eel traps demonstrate sophisticated ecological management.

Budj Bim collapses assumed divides between:

· Geological time

· Ecological time

· Cultural time

It demonstrates that oral tradition can carry temporal knowledge across tens of millennia.

Geology and ancestry intersect.

EVOLUTIONARY TIME — AFRICAN DEEP ORIGINS

The Emergence of Homo sapiens

Human emergence in Africa approximately 300,000 years ago (Hublin et al. 2017) situates humanity within deep evolutionary continuity. Genetic studies confirm ancient southern African lineages (Schlebusch et al. 2017). Symbolic artefacts from Blombos Cave exceed 100,000 years (Henshilwood et al. 2002).

Temporal Awareness Before Agriculture

Hunter-gatherer societies developed temporal awareness through ecological pattern recognition. Seasonal migration, celestial cycles, and generational continuity structured experience.

Time was not abstract.

It was embodied.

GREEK METAPHYSICS AND THE FOUNDATIONS OF WESTERN TEMPORAL THOUGHT

Western philosophy’s systematic engagement with time begins in ancient Greece. The early Greek thinkers did not treat time merely as duration; rather, they interrogated it as a metaphysical problem intimately tied to change, permanence, motion, and being.

Heraclitus: Time as Flux

Heraclitus of Ephesus (c. 535–475 BCE) articulated one of the earliest philosophies of becoming. His doctrine of flux—often summarised in the fragment that one cannot step into the same river twice—positions reality as perpetual transformation. In this view, time is inseparable from change. Stability is an illusion generated by continuity of process.

Heraclitus’ cosmology anticipates later process philosophies and resonates with both thermodynamic irreversibility and Buddhist impermanence. Time is not container but movement itself.

Parmenides: The Denial of Temporal Change

In direct opposition, Parmenides (c. 515–450 BCE) argued that change is illusory. True being is singular, eternal, and unchanging. Motion and temporality belong to deceptive sensory perception.

This radical claim inaugurates a tension that remains central in metaphysics: is time real, or is it an artifact of perception? Contemporary physics echoes this question in block-universe interpretations where past, present, and future coexist in a four-dimensional spacetime manifold.

The Heraclitean-Parmenidean opposition frames the foundational paradox: time as becoming versus time as timeless being.

Plato: Time as the Moving Image of Eternity

In the Timaeus, Plato describes time as “the moving image of eternity.” Eternity is perfect and unchanging; time emerges through celestial motion. The revolutions of the heavenly bodies generate measurable cycles. Thus, time is cosmological, structured by astronomical regularity.

Plato’s cosmology elevates the heavens as temporal regulators. Measurement becomes aligned with cosmic order rather than industrial productivity. This view aligns surprisingly with Indigenous astronomical frameworks such as Wadawurrung sky law.

Aristotle: Time as Number of Motion

Aristotle’s treatment of time in Physics (Book IV) remains one of the most influential classical accounts. He defines time as “the number of motion with respect to before and after.” Time depends upon change, but also upon a mind capable of counting change.

Here, temporality becomes relational: without perception, time is not experienced. Aristotle anticipates psychological constructions of time while grounding temporality in motion.

Importantly, Aristotle also links time to ageing. Biological life unfolds through measurable motion. Growth, decay, and mortality are structured by temporal progression.

Chronos and Kairos

Greek language distinguished between chronos and kairos. Chronos refers to sequential, measurable time—what later becomes clock time. Kairos refers to the opportune, qualitative moment.

Kairos is not duration but significance. It is the “right time,” the moment of decision, revelation, or transformation.

This distinction prefigures the modern contrast between quantitative and qualitative time. Chronos dominates industrial society. Kairos remains embedded in ritual, art, and relational cultures.

Stoicism and Cyclical Recurrence

Stoic philosophers proposed that the cosmos undergoes recurring cycles of destruction and renewal (ekpyrosis). Time is not linear progression but recurring cosmic order. This cyclical temporality parallels Hindu Yuga cycles and Mesoamerican cosmology.

Stoicism also reframed ageing. Mortality was not tragedy but participation in cosmic order.

AUGUSTINE AND THE INTERIORISATION OF TIME

Augustine (397 CE) transformed the philosophy of time by shifting its locus inward. In Confessions (Book XI), he argues that past and future do not exist independently. The past exists as memory, the future as expectation, and the present as attention.

Time becomes psychological.

Augustine anticipates phenomenology by describing temporal experience as a distension of the soul. The present is not a mathematical instant but a field containing retention (memory) and anticipation.

This interiorisation marks a profound shift from cosmological time to experiential time. It bridges Greek metaphysics and modern psychology.

INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIAN TEMPORAL ONTOLOGY

“Everywhen” and Ancestral Coexistence

Anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner (1956) described Indigenous Australian temporality as “everywhen.” Creation is not locked in the past; it coexists with the present. Ancestral beings remain active in landforms, waterways, and constellations.

Time is layered, not linear.

Wadawurrung Sky Law

On Wadawurrung Country, celestial observation structures seasonal cycles. Bunjil, associated in some Kulin traditions with Altair in Aquila (Norris & Hamacher 2014), embodies continuity between creation and astronomical order. Tchingal, the Emu in the Sky formed by dark dust lanes of the Milky Way (Norris & Norris 2009), aligns with emu breeding cycles.

These frameworks demonstrate ecological temporality. Time is read through flowering, migration, and star positioning. It is observational, embodied, and land-based.

Budj Bim as Temporal Convergence

Budj Bim integrates geological eruption (36,900 years ago; Matchan et al. 2020), ecological aquaculture (6,000+ years; UNESCO 2019), and ancestral narrative. It demonstrates continuity across temporal scales.

Indigenous Australian temporality is relational continuity rather than linear succession.

AFRICAN COSMOLOGICAL TEMPORALITIES

The San: Experiential Time

The San of southern Africa structure temporality through ecological knowledge and trance ritual (Lee 1979; Biesele 1993). Age is relational, defined by contribution and knowledge.

Time is not counted but lived.

Yoruba Cosmology

Yoruba metaphysics situates existence between Àiyé (visible realm) and Òrun (ancestral realm). Temporal continuity persists across ontological states. Ancestors remain active within present life.

Time is morally relational and spiritually layered.

Dogon Cosmology

Dogon cosmology integrates celestial cycles into ritual and social organisation. Time unfolds through patterned cosmic order.

Nilotic Age-Sets

Nilotic societies structure time through generational age-sets. Identity emerges through communal progression rather than individual chronology.

Across African traditions, time is ancestral, cyclical, communal.

COMPARATIVE GLOBAL PHILOSOPHIES OF TIME

Daoist Flow

Daoism emphasises alignment with natural cycles. The Dao is rhythmic flow. Time is neither conquered nor commodified; it is harmonised.

This stands in contrast to industrial acceleration.

Buddhist Impermanence

Buddhist philosophy asserts impermanence (anicca) and momentariness. There is no permanent self enduring through time. Existence unfolds as conditioned arising.

This resonates with Heraclitean flux and contemporary process philosophy.=

QUANTITATIVE AND QUALITATIVE TIME — POLITICAL ECONOMY OF TEMPORALITY

A decisive transformation in the philosophy of time occurs with the rise of industrial modernity. Time becomes quantified. It is standardised, segmented, synchronised, monetised. Mechanical clocks in medieval Europe (Landes 1983) detach daily life from seasonal rhythms. Railway timetables impose uniform coordination across geography. The International Meridian Conference of 1884 globalises standard time.

Time becomes abstract.

Quantitative time is numerical, measurable, divisible. It is compatible with industrial capitalism because it allows labour to be calculated. The aphorism “time is money” signals a profound shift: time is no longer experienced but expended.

This transformation produces what may be called temporal abstraction—time detached from ecology and embedded in economic systems.

In contrast, qualitative time remains experiential, ecological, and relational. Indigenous frameworks such as Wadawurrung seasonal knowledge interpret time through flowering cycles, animal migrations, and celestial orientation (Norris & Hamacher 2014). Chronos yields to kairos.

The dominance of quantitative temporality reshapes consciousness itself. It restructures governance, education, work, and even self-perception.

Time becomes resource.

BERGSON AND LIVED DURATION

Henri Bergson’s critique of spatialised time provides a philosophical counterpoint to industrial abstraction. In Time and Free Will (1889), Bergson distinguishes between measurable time and lived duration (durée). Measured time divides experience into homogeneous units. Duration, by contrast, is qualitative and indivisible. The past persists within the present; memory is not stored behind us but coexists in consciousness.

For Bergson, the attempt to measure time reduces it to space. Real time flows.

This insight parallels Indigenous “everywhen” and Daoist flow. It also anticipates contemporary neuroscience, which reveals that memory density alters perceived duration (Wittmann 2016).

Duration resists commodification.

HEIDEGGER AND EXISTENTIAL TEMPORALITY

Martin Heidegger radicalises the problem by arguing that temporality is the structure of existence itself (Being and Time, 1927). Humans (Dasein) are beings stretched between thrownness (past), engagement (present), and projection (future). Time is not a container in which life unfolds; it is the condition of possibility for meaning.

Heidegger critiques everyday clock time as inauthentic temporality. Authentic existence requires confrontation with finitude—awareness that life is bounded.

Time defines mortality.

Ageing, in this framework, is not decline but unfolding toward finitude.

HUSSERL AND THE STRUCTURE OF THE PRESENT

Edmund Husserl deepens temporal phenomenology by describing retention (immediate past) and protention (anticipation of immediate future). The present is not a point but a field. Consciousness stretches.

Augustine anticipated this insight; neuroscience confirms it (Wittmann 2016). Temporal awareness is constructed through overlapping layers of memory and expectation.

The “now” is thick.

PSYCHOLOGICAL TIME AND NEUROSCIENCE

Temporal perception arises from distributed neural systems involving the basal ganglia, cerebellum, and cortical networks (Wittmann 2016). There is no single time centre. Duration perception shifts with emotion and attention.

Fear increases temporal density; events appear prolonged. Novelty expands retrospective duration because more distinct memories are encoded. Routine compresses experience.

Psychological time is elastic.

This elasticity reveals that time, at the level of lived experience, is constructed.

AGEING AND TEMPORAL COMPRESSION

The widespread perception that time accelerates with age can be explained through several mechanisms. Proportional lifespan theory suggests that each year becomes a smaller fraction of lived experience (James 1890). Reduced novelty decreases memory density. Predictive neural automation reduces conscious encoding.

At age five, one year represents 20% of life lived. At age fifty, it represents 2%.

Time does not accelerate.

Perception shifts.

Ritual, travel, creativity, and ecological engagement reintroduce novelty and expand subjective duration.

SOCIAL ACCELERATION AND MODERNITY

Hartmut Rosa (2013) argues that modern societies are characterised by escalating technological, economic, and social acceleration. Efficiency increases, yet perceived time scarcity intensifies. Digital communication collapses boundaries. Work extends beyond location. Productivity metrics fragment continuity.

Acceleration produces alienation.

Indigenous and relational temporal frameworks restore resonance—connection between self, community, and environment.

Acceleration fragments.

Relational temporality integrates.

SYNTHESIS — TOWARD A RELATIONAL TEMPORAL ONTOLOGY

Across scales, time appears in multiple forms:

Cosmological time begins with the Big Bang (Planck Collaboration 2020).

Geological time erupts at Budj Bim (Matchan et al. 2020).

Evolutionary time unfolds across 300,000 years (Hublin et al. 2017).

Ancestral time persists in Indigenous cosmologies (Stanner 1956).

Metaphysical time oscillates between flux and permanence (Heraclitus; Parmenides).

Existential time structures being (Heidegger 1927).

Psychological time stretches and compresses (Wittmann 2016).

Industrial time fragments experience (Landes 1983).

No single framework exhausts time.

Time is relational structure across scales.

TIME IN THE ANTHROPOCENE

The Anthropocene introduces a new temporal crisis. Human industrial activity alters geological systems within centuries rather than millennia. Climate change compresses geological processes into political timescales.

Modern acceleration collides with deep time.

Relational temporal consciousness becomes necessary for sustainability. Recognising humanity within 13.8 billion years of cosmic unfolding and 300,000 years of evolutionary continuity reframes responsibility.

Temporal humility emerges.

CONCLUSION: TIME AS BELONGING

From the emergence of spacetime 13.8 billion years ago to the volcanic memory of Budj Bim; from Heraclitean flux to Daoist flow; from Bergsonian duration to Heideggerian finitude; from African deep ancestry to Wadawurrung sky law; from psychological elasticity to social acceleration—time reveals itself as multidimensional.

Physics explains its structure.

Philosophy explores its meaning.

Psychology reveals its elasticity.

Indigenous knowledge embeds it in land and sky.

Time is not merely something that passes, it’s living in every moment.

REFERENCE LIST

Aristotle 350 BCE, Physics.

Augustine 397 CE, Confessions.

Aveni, A 2001, Skywatchers, University of Texas Press.

Bergson, H 1889, Time and Free Will.

Biesele, M 1993, Women Like Meat.

Clarkson, C et al. 2017, ‘Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago’, Nature.

Einstein, A 1916, Relativity: The Special and the General Theory.

Flood, G 1996, An Introduction to Hinduism.

Hawking, S 1988, A Brief History of Time.

Heidegger, M 1927, Being and Time.

Henshilwood, C et al. 2002, ‘Emergence of modern human behavior’, Science.

Hublin, JJ et al. 2017, ‘New fossils from Jebel Irhoud’, Nature.

Husserl, E 1928, On the Phenomenology of the Consciousness of Internal Time.

James, W 1890, The Principles of Psychology.

Landes, D 1983, Revolution in Time.

Lee, R 1979, The !Kung San.

Matchan, EL et al. 2020, ‘Early eruption of Budj Bim volcano’, Geology.

Norris, R & Hamacher, D 2014, ‘Astronomy of Aboriginal Australia’.

Norris, R & Norris, C 2009, Emu Dreaming.

Oxford English Dictionary 2024, ‘Time’.

Planck Collaboration 2020, ‘Planck 2018 results’.

Rosa, H 2013, Social Acceleration.

Rovelli, C 2018, The Order of Time.

Schlebusch, C et al. 2017, ‘Southern African ancient genomes’, Science.

Stanner, WEH 1956, ‘The Dreaming’.

UNESCO 2019, Budj Bim Cultural Landscape.

Whitrow, GJ 1988, Time in History.

Wittmann, M 2016, Felt Time.

Researched by James Vegter (17th, February, 2026)

MLA

Sharing the truth of Indigenous and colonial history through film, education, land, and community.

www.magiclandsalliance.org

Copyright MLA – 2025

Magic Lands Alliance acknowledges the Traditional Owners, Custodians, and First Nations communities across Australia and internationally. We honour their enduring connection to the sky, land, waters, language, and culture. We pay respect to Elders past, present, and emerging, and to all First Peoples’ communities and language groups. This article draws only on publicly available information; many cultural practices remain the intellectual property of their respective communities.

POWER

History of Power

Philosophical and Historical Analysis of Language, Law, Land, Body, and Consciousness of Power

MLA Educational Series

James Vegter

Magic Lands Alliance – MLA Educational Series

18 February 2026

The word power originates from the Latin posse (“to be able”) and entered English through Old French during the thirteenth century (Oxford English Dictionary 2024). Initially denoting capacity or ability, its meaning expanded over centuries to signify authority, sovereignty, domination, and institutional control. In the context of Australian colonisation, power shifted from abstract capability to structured force embedded in legal doctrine, land appropriation, frontier violence, economic redistribution, and assimilation policy. This interdisciplinary paper situates the concept of power within linguistic history, political philosophy, colonial law, economics, neuroscience, and contemporary digital society. Drawing on the work of Friedrich Nietzsche, Michel Foucault, Hannah Arendt, Pierre Bourdieu, and modern neurobiological research, it argues that power is not merely political—it is structural, embodied, relational, and productive. Through Australian case studies including terra nullius, the Batman Treaty, frontier massacres, and the Stolen Generations, this article demonstrates how language and law functioned as mechanisms of dominance while also exploring alternative models of relational authority grounded in Indigenous knowledge systems.

I. Linguistic and Philosophical Origins of Power

The English noun power derives from Latin posse (“to be able”) and potentia (“ability, force, capacity”), transmitted through Old French poeir or pouvoir before entering Middle English around c. 1300 (Oxford English Dictionary 2024; Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries n.d.). In early usage, the term referred simply to capability or potential. Over time, however, it expanded to denote authority to command, jurisdiction to govern, and the right to exercise control. This semantic expansion coincided with the consolidation of monarchies in medieval Europe, where feudal fragmentation gradually gave way to centralised state authority (Skinner 1978).

Philosophically, power became intertwined with sovereignty. Jean Bodin’s sixteenth-century theory of sovereignty defined supreme authority as indivisible and absolute within territorial boundaries. Thomas Hobbes later argued in Leviathan (1651) that peace required submission to a sovereign capable of preventing chaos. Language thus evolved alongside political consolidation; the transformation of the word power mirrors the transformation of political organisation itself.

Friedrich Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morality (1887) offers a critical method for examining this transformation. Nietzsche contends that moral and political concepts arise from historical struggles rather than neutral reasoning. His concept of the “will to power” refers not merely to domination but to a fundamental drive toward growth, expansion, and self-assertion (Nietzsche 1887/1967). Yet Nietzsche also warns that moral language often disguises power relations. Terms such as “civilisation,” “progress,” and “order” can conceal hierarchical imposition. This insight proves particularly relevant in analysing colonial discourse.

II. Sovereignty and the Colonial State

British colonisation of Australia required not merely physical occupation but juridical legitimation. Sovereignty was proclaimed in 1788 without treaty or consent from Indigenous nations (Reynolds 1987). The British Crown asserted radical title over land, positioning itself as the ultimate legal authority. Under European jurisprudence, sovereignty signified supreme and indivisible authority over territory (Bodin 1576/1992). Indigenous governance systems, despite their sophistication, were not recognised as sovereign entities within this framework.

Power thus operated across multiple dimensions: discursive (legal language), juridical (sovereign authority), administrative (governance and policy), and military (enforcement). Michel Foucault’s concept of power/knowledge clarifies this process. In Discipline and Punish (1975), Foucault argues that power produces knowledge and shapes reality through classification and institutional norms. Colonial sovereignty did not simply displace Indigenous law; it replaced relational land systems with property regimes defined through cadastral mapping and documentation (Harley 1988).

III. Terra Nullius as Linguistic Power

The doctrine of terra nullius, meaning “land of no one,” classified Australia as legally unoccupied because it did not reflect European agricultural systems (Australian Museum n.d.; Reynolds 1987). Although Indigenous nations maintained complex systems of law and custodianship, British law deemed the land legally empty. This classification was not descriptive but constitutive—it created the legal conditions for appropriation.

The High Court’s decision in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) on 3 June 1992 overturned terra nullius, recognising that Indigenous law and land rights predated British sovereignty (AIATSIS 2025; National Museum of Australia n.d.). Yet for over two centuries, the doctrine structured property relations. Foucault’s framework demonstrates how legal discourse produced material consequences; a phrase reshaped an entire continent’s political and economic order.

Hannah Arendt’s distinction between power and violence further illuminates this history. In On Violence (1970), Arendt argues that genuine power arises from collective legitimacy, whereas violence appears when authority is insecure. Colonial rule relied initially on legal fiction; when contested, violence enforced it.

IV. Frontier Violence and Spatial Control

The University of Newcastle Colonial Frontier Massacres Project documents 438 massacre events between 1788 and 1930, including 424 involving Aboriginal victims. Violence functioned as territorial enforcement. Following displacement, land was surveyed and titled, transforming Country into private property. As Harley (1988) argues, maps are political instruments that construct authority. Surveying and fencing institutionalised domination spatially.

Control of land required control of bodies. Violence and legality operated together: force cleared territory; law formalised ownership.

V. Economic Capital and Structural Inequality

Colonial dispossession translated into enduring economic advantage. Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of capital distinguishes economic, social, cultural, and symbolic forms (Bourdieu 1986). Land acquisition provided economic capital, which generated social networks and cultural legitimacy. Wealth accumulated intergenerationally within settler populations. Contemporary disparities in land ownership, wealth distribution, and institutional representation reflect this historical redistribution (Piketty 2014).

Economic power today extends beyond states into multinational corporations and financial systems. Global capitalism reconfigures sovereignty around capital flows rather than territorial control. Power increasingly resides in markets and data infrastructures.

VI. Biopolitics and the Stolen Generations

From the late nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century, Australian legislation authorised the forced removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (AHRC 1997). Foucault’s concept of biopolitics describes state regulation of life, reproduction, and population (Foucault 1976). The Stolen Generations illustrate power operating at the level of identity, family, and memory.

Administrative systems reshaped culture through schooling, labour training, and assimilation policy. Power extended from territorial governance into psychological governance.

VII. Modern Interpretations of Power

In contemporary society, power circulates through economic concentration, media influence, digital surveillance, racial inequality, and symbolic capital. Social media platforms shape discourse through algorithmic amplification, a phenomenon sometimes described as “surveillance capitalism” (Zuboff 2019). Information control has become a primary structural mechanism of influence.

Statistical disparities in health, incarceration, and employment illustrate enduring structural inequalities affecting Indigenous communities (AIATSIS 2025). Power persists through policy design, funding structures, and institutional norms.

Spiritual authority, by contrast, offers alternative models. In many Indigenous contexts, Eldership reflects custodial responsibility rather than coercion (Broome 2005). Authority derives from knowledge and relational accountability.

VIII. Neuroscience, Hierarchy, and Embodied Power

Power is not merely institutional; it is embodied. Research in primatology demonstrates that social hierarchy influences stress hormones and health outcomes (Sapolsky 2005). Perceived power correlates with dopamine activation and reduced cortisol levels (Keltner, Gruenfeld & Anderson 2003). Chronic powerlessness correlates with stress-related illness.

Structural inequality therefore embeds itself biologically. Colonial trauma can be understood not only socially but physiologically.

IX. Ethical Frameworks: Power Over, With, and Within

A critical distinction can be drawn between three forms of power:

· Power Over – domination, coercion, hierarchy

· Power With – shared governance, collaboration

· Power Within – cultural resilience, identity, knowledge

Educational reform and Treaty processes aim to shift from domination toward relational authority.

Conclusion

The word power began as “ability.” Through European political consolidation and colonial expansion, it evolved into sovereignty and structured dominance. In Australia, power operated through law, mapping, violence, economic allocation, and assimilation policy. In modern society, it extends through capital, digital systems, race, and neurobiology.

Philosophical analysis reveals that power is not inherently oppressive. It becomes oppressive when detached from legitimacy and reciprocity. Transformative models of governance require movement from domination toward relational and ethical forms of authority.

Power is historically constructed, biologically embodied, and ethically transformable.

Appendix

Foucault vs Nietzsche: A Comparative Analysis of Power

Friedrich Nietzsche and Michel Foucault are frequently linked in discussions of power, yet their conceptions differ significantly in scope, method, and ethical orientation.

1. Genealogy and Method

Nietzsche pioneered genealogical critique, arguing that moral concepts emerge from historical struggles rather than divine or rational origins (Nietzsche 1887/1967). Foucault adopted and expanded this genealogical method, applying it to institutions such as prisons, hospitals, and schools (Foucault 1975).

Both reject universal moral foundations. However, Nietzsche emphasises psychological drives, whereas Foucault analyses institutional structures.

2. The Will to Power vs Power/Knowledge

Nietzsche’s “will to power” describes an existential drive toward expansion and creative self-overcoming. It is ontological—embedded in life itself.

Foucault’s conception is structural and relational. Power is not possessed but exercised through networks. It produces knowledge, norms, and subjectivity (Foucault 1976).

In colonial analysis, Nietzsche illuminates ambition and domination at the level of desire. Foucault explains how institutions stabilise domination through discourse.

3. Power and Morality

Nietzsche critiques herd morality and valorises self-overcoming. Foucault refrains from prescribing morality, instead analysing how regimes of truth shape behaviour.

Hannah Arendt adds a third dimension: she distinguishes power from violence, arguing that power depends on collective legitimacy (Arendt 1970).

Together, these thinkers provide a layered understanding:

· Nietzsche: power as existential drive

· Foucault: power as structural network

· Arendt: power as collective legitimacy

4. Implications for Colonial and Modern Analysis

Nietzsche helps explain imperial ambition. Foucault explains administrative control. Arendt explains legitimacy crises.

An integrated framework suggests that power operates simultaneously at:

· The level of desire (Nietzsche)

· The level of discourse (Foucault)

· The level of collective authority (Arendt)

Understanding these dimensions enables critical reflection on both colonial history and modern digital governance.

Extended References

Arendt, H. (1970) On Violence.

Bodin, J. (1576/1992) On Sovereignty.

Bourdieu, P. (1986) ‘The Forms of Capital.’

Broome, R. (2005) Aboriginal Victorians.

Foucault, M. (1975) Discipline and Punish.

Foucault, M. (1976) The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1.

Harley, J.B. (1988) ‘Maps, Knowledge, and Power.’

Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D., & Anderson, C. (2003) ‘Power, Approach, and Inhibition.’

Nietzsche, F. (1887/1967) On the Genealogy of Morality.

Piketty, T. (2014) Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

Reynolds, H. (1987) The Law of the Land.

Sapolsky, R. (2005) ‘The Influence of Social Hierarchy on Primate Health.’

Zuboff, S. (2019) The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

Oxford English Dictionary (2024) ‘Power’.

AIATSIS (2025) The Mabo Case.

AHRC (1997) Bringing Them Home Report.

Written, Researched and Directed by James Vegter (17th, February, 2026)

MLA

Sharing the truth of Indigenous and colonial history through film, education, land, and community.

www.magiclandsalliance.org

Copyright MLA – 2025

Magic Lands Alliance acknowledges the Traditional Owners, Custodians, and First Nations communities across Australia and internationally. We honour their enduring connection to the sky, land, waters, language, and culture. We pay respect to Elders past, present, and emerging, and to all First Peoples’ communities and language groups. This article draws only on publicly available information; many cultural practices remain the intellectual property of their respective communities.

SUPERPOWERS

SuperPower Concept through History

CYCLES OF GLOBAL DOMINANCE: Empire, Economy, War, Population, and Indigenous Sovereignty

MLA Educational Series

Written by James Vegter

Magic Lands Alliance – Advanced Research

18 February 2026

Abstract

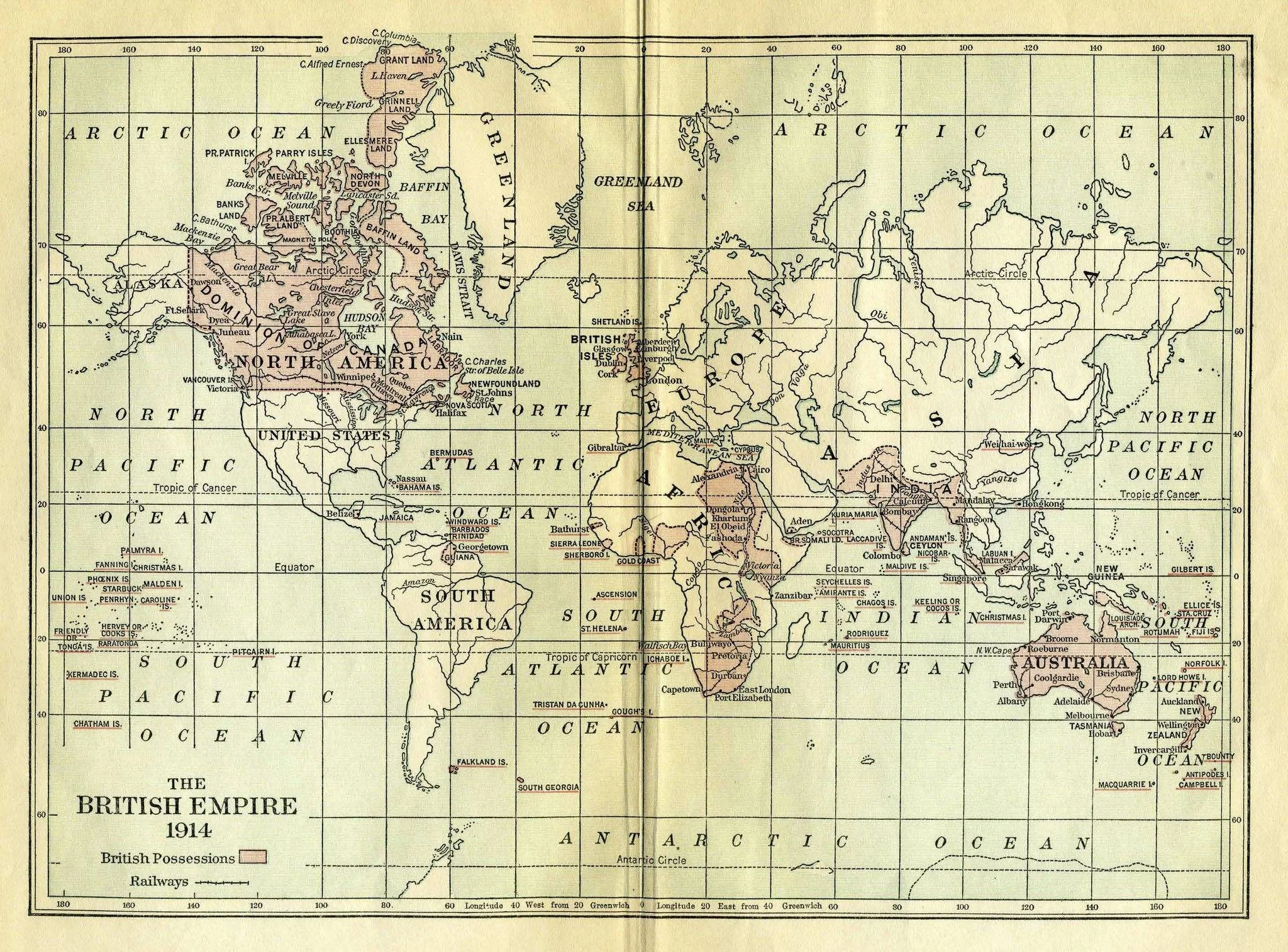

Throughout recorded history, global dominance has shifted among empires and nation-states in recurring structural cycles shaped by war, demography, technology, and economic integration. From the Achaemenid Persians and Mauryan India to Rome, the Islamic Caliphates, the Mongols, Iberian maritime empires, the Dutch Republic, the British Empire, the United States, the Soviet Union, and the contemporary rise of China and India, political power has repeatedly consolidated and fragmented. This revised MLA educational paper presents a paragraph-driven geopolitical analysis of these cycles, integrating economic statistics, population modelling, military transformation, and Indigenous perspectives on sovereignty. It further includes dedicated sections on the role of war in reshaping power and on Australia’s contemporary geopolitical position within the Indo-Pacific. The study argues that superpower dominance is neither permanent nor linear but evolves through structural pressures—technological shifts, demographic transitions, economic scale, environmental stress, and resistance movements.

I. Introduction: The Cyclical Nature of Global Power

Power has never been static. Across millennia, states rise to prominence through combinations of military capacity, economic expansion, demographic strength, and institutional coherence. They decline when these same foundations weaken. Historians such as Paul Kennedy (1987) describe this phenomenon as “imperial overstretch,” where military commitments outpace economic capacity. Giovanni Arrighi (1994) similarly identifies long cycles of hegemonic accumulation—Genoese, Dutch, British, American—each linked to financial innovation and trade expansion.

Although power shifts do not occur in exact century-long intervals, major restructurings often unfold over 100–300 year phases. These shifts are shaped by:

Technological breakthroughs

Trade route dominance

Energy transitions

Population growth or decline

Military innovation

Financial systems

Institutional adaptability

Superpower status, therefore, is conditional rather than permanent.

II. Early Civilisations and the Foundations of Power (c. 2000 BCE–500 CE)

The earliest empires emerged from agricultural revolutions that enabled population density and surplus production. Control of irrigation systems in Mesopotamia and Egypt provided not only food but political legitimacy (Harari 2014). By 1 CE, the world’s population is estimated at between 170 and 300 million (Maddison 2007).

The Achaemenid Empire (c. 550–330 BCE) governed nearly half the world’s population at its height (Briant 2002). Its decentralised satrap system allowed administrative flexibility across vast territories. This capacity to govern diversity was central to its longevity.

In South Asia, the Mauryan Empire (c. 322–185 BCE) unified much of the Indian subcontinent. Under Ashoka, it administered one of the largest populations of the ancient world (Thapar 2002). India represented roughly one-third of global economic output around 1 CE (Maddison 2007), underscoring how demographic concentration often correlates with economic power.

The Roman Empire similarly integrated infrastructure, law, and military professionalism. At its peak, Rome controlled 60–70 million people and up to 20–30% of global GDP (Scheidel 2007). However, fiscal strain, territorial overstretch, and internal instability contributed to its fragmentation.

Ancient cycles reveal a recurring pattern: expansion through military superiority and integration through administrative systems, followed by decline when economic burdens exceed productive capacity.

III. Medieval Transitions and Trade Networks (500–1500 CE)

Following Rome’s decline, regional powers restructured global influence. The Byzantine Empire preserved Roman administrative continuity, while Islamic caliphates expanded rapidly across North Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia. The Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258) connected Europe, Africa, and Asia through trade and intellectual exchange.

The Mongol Empire (1206–1368) became the largest contiguous land empire in history. Although militarily formidable, it lacked institutional integration necessary for long-term cohesion. World population around 1300 reached approximately 400 million, though the Black Death would dramatically reduce numbers across Eurasia.

This period demonstrates that trade networks—not only territorial conquest—can sustain power. Control of the Silk Road was as influential as battlefield dominance.

IV. Maritime Empires and Early Globalisation (1500–1700)

European maritime expansion marked a shift from land-based empires to oceanic dominance. Spain and Portugal expanded globally through navigation advances. Silver extraction from the Americas reshaped global monetary flows.

The Dutch Republic pioneered financial capitalism. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) operated as a corporate-state hybrid, demonstrating how commercial power could rival military empires (Arrighi 1994). Financial innovation increasingly replaced territorial conquest as the primary source of influence.

V. The British Empire and Industrial Hegemony (1700–1914)

The British Empire reached its territorial height in 1914. Industrialisation transformed Britain into the “workshop of the world.” By 1820, British per capita GDP exceeded most regions globally (Maddison 2007). By 1913, Britain and its empire accounted for roughly 23% of global GDP.

Industrial coal energy, naval supremacy, and financial dominance through London banking allowed Britain to integrate trade networks spanning India, Africa, and the Pacific.

World population grew from approximately 1 billion in 1800 to 1.6 billion in 1900. Population expansion intensified labour supply and colonial settlement patterns.

VI. War as a Catalyst for Power Restructuring

War has repeatedly accelerated power transitions. Military conflict redistributes economic resources, destroys old hierarchies, and enables new states to rise.

Examples include:

The Peloponnesian War weakening Athens.

The Napoleonic Wars restructuring Europe.

World War I dismantling empires (Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian).

World War II transferring dominance from Europe to the United States and the Soviet Union.

After 1945, the United States accounted for nearly 50% of global industrial output (Kennedy 1987). Nuclear technology introduced deterrence as a new dimension of power.

Wars reveal that technological innovation often emerges through conflict. Iron metallurgy, gunpowder, industrial weapons production, nuclear physics, and cyber warfare each reshaped geopolitical structures.

VII. Twentieth-Century Bipolarity and Demographic Expansion

The Cold War institutionalised bipolar power between the United States and the Soviet Union. Ideological competition between capitalism and communism shaped global alliances.