Indigenous Languages and Clan Groups in Victoria: A Focus on the Wadawurrung

Before colonisation, Victoria was home to a rich diversity of Indigenous languages, spoken across dozens of nations and hundreds of clan groups. Each language reflected deep relationships between people, Country, and spirit. Language was not merely a tool of communication but a living record of law, kinship, ceremony, and ecological knowledge. Words carried stories of the land, the seasons, and the animals — encoding millennia of scientific observation and spiritual understanding.

Colonisation brought devastating disruption. Violence, disease, forced removals, and assimilation policies — including bans on language use — led to the silencing of many languages and the fracturing of traditional social systems. Yet, today, many Victorian communities are engaged in revival programs, ensuring that language remains central to cultural identity and survival. This article explores the Indigenous languages of Victoria, the role of clan-based organisation, and focuses particularly on the enduring language and culture of the Wadawurrung people of south-western Victoria.

Languages of Victoria

Pre-Contact Diversity

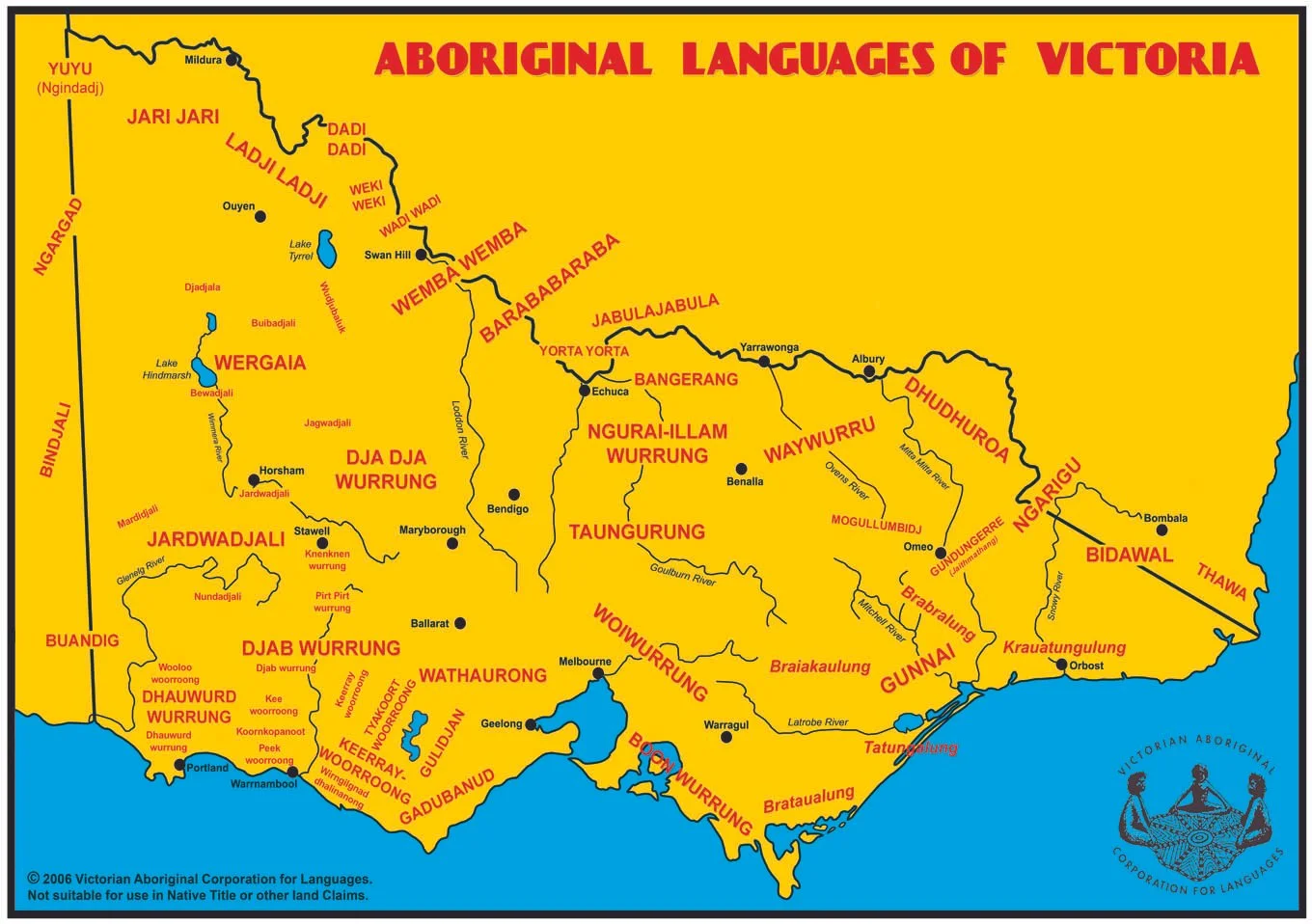

Prior to European invasion, Victoria is estimated to have had around forty Indigenous languages and over one hundred dialects (Clark, 1990). These languages formed part of larger regional families, including those of the Kulin, Gunditjmara, and Eastern Victorian language groups. Among these were the Woiwurrung spoken by the Wurundjeri of the Melbourne region, Boonwurrung across the Mornington Peninsula and coastal bays, Wadawurrung spanning Geelong and Ballarat, Taungurung across the central ranges, and Gunditjmara and Dhauwurd Wurrung in the south-west near Portland.

Each language expressed a world view specific to its Country. For example, “Wadawurrung” itself means “Wattle Language” — from wada, meaning wattle, and wurrung, meaning tongue or speech. Language was not a neutral or abstract medium: it was inseparable from law (lore), kinship, ceremony, and ecological management. Terms for the seasons guided when to fish, gather murnong (yam daisy), or harvest eels. Place names described the shape and character of the land — living maps linking memory to environment and spirit.

Language as Knowledge

Victorian Indigenous languages contained highly sophisticated systems of classification and observation. The vocabulary of each nation revealed an intricate understanding of ecology and cosmology. For instance, words often described subtle variations in weather, the behaviour of animals, or the ripening of plants — acting as seasonal calendars that signalled sustainable practices.

Kinship terminology was equally detailed. Every word for mother, uncle, sibling, or in-law defined obligations, marriage rules, and patterns of respect. Language thus encoded systems of governance, law, and environmental ethics. Through songs, storytelling, and ceremony, these words preserved both practical knowledge and sacred law.

Clan Groups and Social Organisation

In Victoria, Indigenous societies were structured into nations, each with its own language and distinct territories. Within each nation were multiple clans, which held custodial rights to specific rivers, mountains, or tracts of Country. These clans were often named for prominent landscape features or totemic species and were linked by shared ceremonies and trade routes.

The Kulin Nations — which included the Woiwurrung, Boonwurrung, Taungurung, Dja Dja Wurrung, and Wadawurrung — shared a sophisticated system of social law. Society was divided into two great moieties: Bunjil (the wedge-tailed eagle) and Waang (the crow). Each person belonged to one moiety, and marriage had to occur with someone of the opposite moiety. This ensured both social balance and ecological reciprocity, as moiety affiliations extended beyond humans to animals, plants, and celestial beings (Barwick, 1998; Broome, 2005).

The Wadawurrung People

Country and Language

The Wadawurrung, also spelled Wathaurong or Wathawurrung, are the Traditional Owners of lands stretching from the Great Dividing Range near Ballarat, across Geelong, the Bellarine Peninsula, and along the Surf Coast to the western volcanic plains. Their language is part of the Kulin family and is closely related to Woiwurrung and Boonwurrung (Blake, 1991).

The Wadawurrung language is deeply interwoven with landscape. Words and place names hold precise meanings that describe physical features, ecological relationships, and spiritual histories. Djilang, the original name for Geelong, translates to “tongue of land,” referring to the peninsula that extends into Corio Bay — a site of gathering and ceremony. Moorabool means “shadow” or “ghost,” associated with the cool mists and spirits of the river valley. Ballarat, derived from Balla Arat, means “resting place” or “place to rest,” acknowledging its ancient use as a camping and meeting area near waterholes. Werribee, or Wirribi Yaluk, means “backbone river,” symbolising the life-giving connection of the river system to the surrounding Country.

Further along the coast, Kuarka-dorla, the Wadawurrung name for the Spring Creek area near Torquay, means “sandy place,” describing the dunes and seasonal camping grounds used by coastal clans. The You Yangs, or Wurdi Youang, translates to “big mountain shaped like a circle” or “mountain shaped like a mountain” — a sacred site used for astronomical observation and ceremony. Such names illustrate that every word was a lesson in geography, astronomy, and ancestral law, connecting land, language, and lineage in one system of knowledge.

Clan Groups and Responsibilities

The Wadawurrung Nation historically comprised around twenty-five clan groups, each responsible for caring for a particular region of Country. Clans managed resources through sustainable practices, guided by ceremony, law, and ecological knowledge. The Bunjil and Waang moiety system governed marriage and social responsibility, ensuring balance between people and environment.

Important ceremonial and economic sites included Mount Buninyong, regarded as sacred to ancestral beings; Balyang on the Barwon River, a renowned eel-fishing area; and Wurdi Youang, a remarkable stone arrangement aligned with solar movements. These places demonstrate the integration of astronomy, engineering, and spirituality within Wadawurrung culture.

Colonisation and Dispossession

The arrival of colonists in the 1830s brought rapid dispossession to the Wadawurrung people. Geelong, Ballarat, and surrounding districts became centres of settlement and gold-rush expansion, resulting in violence, disease, and forced displacement. Frontier massacres and land theft decimated populations, while missions such as Coranderrk and Framlingham gathered survivors from across multiple nations (Clark, 1995).

With these disruptions came the near-eradication of language. By the late nineteenth century, Wadawurrung speech was considered “extinct” by colonial authorities. However, linguistic notes, wordlists, and oral memory survived — carefully preserved by families and later by researchers such as Blake (1991). These fragments would form the basis for the modern revival movement.

Language Revival Today

In the twenty-first century, the Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation (WTOAC) is leading a resurgence of language, ensuring its reintegration into education, community life, and public spaces. Classes are now taught in schools and cultural centres across Geelong and Ballarat. Traditional place names are being reinstated, restoring Djilang, Balla Arat, and Wurdi Youang to the public landscape. Songs, dances, and oral histories are being retaught in language, reuniting families with ancestral speech.

This revival is part of a broader statewide initiative to reclaim Indigenous languages in Victoria, supported by the First Peoples’ Assembly and cultural institutions such as AIATSIS. Through naming projects, digital archives, and collaborative dictionaries, the voices of Country are being heard again — not as relics of the past, but as living expressions of law, identity, and belonging.

Global Analogies

The suppression and revitalisation of Indigenous languages in Victoria mirrors similar struggles worldwide. In North America, First Nations languages once targeted by residential school policies are now being reclaimed through immersion schools and digital education (TRC Canada, 2015). In Aotearoa New Zealand, Te Reo Māori has flourished through Kōhanga Reo (language nests) and bilingual schooling (Walker, 1990). Likewise, in Hawai‘i, the Hawaiian language has been revitalised through community immersion programs, restoring cultural confidence and continuity.

These global movements demonstrate that language revival is both possible and transformative. Each restored word reconnects generations and reawakens the worldview of a people who have never ceased belonging to their land.

Conclusion

The Indigenous languages of Victoria once resonated across plains, forests, and coasts — a chorus of voices shaping law, memory, and connection to Country. Colonisation brought silence, but it did not erase knowledge. The endurance of communities such as the Wadawurrung shows that language revival is an act of renewal and truth-telling.

Each word spoken — Djilang, Wurdi Youang, Ballarat, Balyang — carries the breath of ancestors and the science of place. Reviving language is not simply reclaiming words; it is restoring a living relationship between people and Country, ensuring that future generations inherit the knowledge, identity, and spirit carried within them.

References

Barwick, D. (1998). Rebellion at Coranderrk. Canberra: Aboriginal History Monograph.

Blake, B. (1991). Wathawurrung and the Colac Language of Southern Victoria. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Broome, R. (2005). Aboriginal Victorians: A History Since 1800. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Clark, I. (1990). Aboriginal Languages and Clans: An Historical Atlas of Western and Central Victoria, 1800–1900. Melbourne: Monash Publications in Geography.

Clark, I. (1995). Scars in the Landscape: A Register of Massacre Sites in Western Victoria 1803–1859. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report. Ottawa: TRC Canada.

Walker, R. (1990). Ka Whawhai Tonu Matou: Struggle Without End. Auckland: Penguin.

Written, Researched and Directed by James Vegter and Uncle Reg Abrahams 16/09/2025.

MLA

Sharing the truth of Indigenous and colonial history through film, education, land and community.

Copyright of MLA – 2025

Magic Lands Alliance acknowledge the Traditional Owners, Custodians, and First Nations communities across Australia and internationally. We honour their enduring connection to the sky, land, waters, language, and culture. We pay our respects to Elders past, present, and emerging, and to all First Peoples communities and language groups. This article draws only on publicly available information; many cultural practices remain the intellectual property of communities.