Beneath the Land: The Earth’s Layers, Soils, and Stories of Country in Victoria

Beneath every step on Victorian Country lies a deep history written in stone, soil, and fire. The Earth’s crust — where life takes root — is only the thin outer layer of a vast planet formed from molten rock, metal, and mineral over 4.5 billion years. From the surface soils that sustain eucalypt forests and farmlands to the molten iron of the core that generates Earth’s magnetic field, this layered structure holds both scientific and cultural meaning.

For Indigenous peoples such as the Wadawurrung, understanding what lies beneath was not only practical but spiritual. Knowledge of soils, minerals, and underground water was woven into story, ceremony, and law. The layers of the Earth were seen as layers of Country — living systems with spirit, memory, and responsibility.

The Science of the Earth Beneath Us

The Layers of the Earth

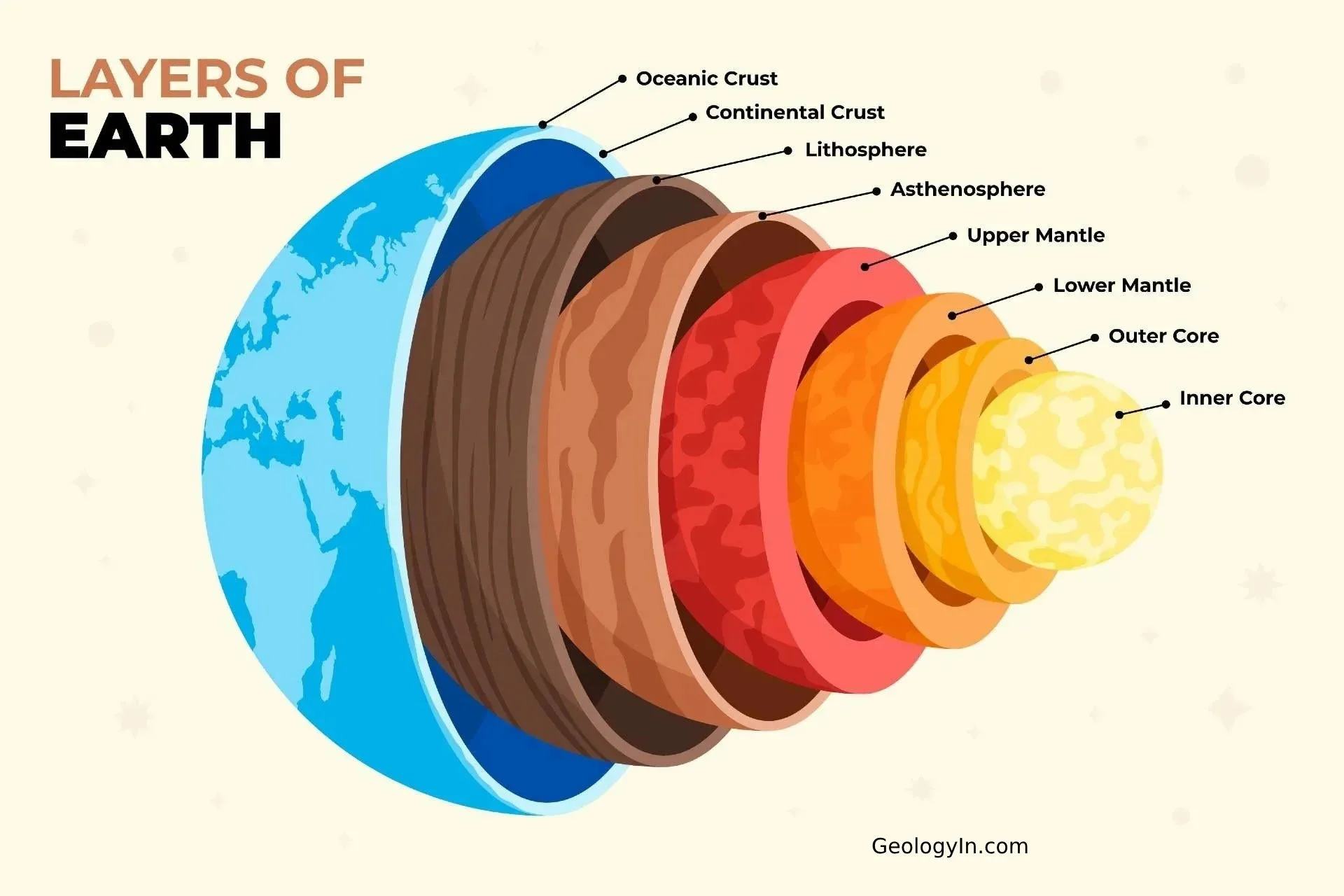

Scientists describe the Earth as having four main layers, each distinct in composition and temperature:

Crust – The solid outer shell, made of rock, soil, and ocean floor. It’s only about 5–70 kilometres thick.

Mantle – A layer of hot, semi-solid rock that slowly moves over millions of years, driving tectonic shifts and volcanoes.

Outer Core – A liquid layer of molten iron and nickel that produces Earth’s magnetic field.

Inner Core – A solid sphere of iron and nickel, about as hot as the surface of the sun (over 5,000°C).

The crust beneath Victoria formed through ancient geological processes — volcanic eruptions, tectonic collisions, and erosion. These forces created the state’s diverse landforms: mountains, plains, valleys, and coasts.

Geology of Victoria

Victoria’s land is a mosaic of ancient continental fragments welded together over hundreds of millions of years.

Eastern Victoria (e.g., Gippsland) formed from marine sediments uplifted by tectonic activity.

Central Victoria (including Wadawurrung Country) is defined by the Western Victorian Volcanic Plains, created by lava flows over the past 5 million years.

Western Victoria includes the Grampians (Gariwerd), formed from sandstone uplifted by faulting and erosion.

These regions together tell the geological story of fire, pressure, and water shaping Country — a living map beneath our feet.

Soils of Victoria: Colour, Life, and Memory

Soils are more than dirt — they are the thin living skin of the Earth, made from rock, minerals, organic matter, and countless microorganisms.

Types of Victorian Soils

Basaltic Soils (Volcanic Plains): Rich, dark-red soils formed from weathered lava; fertile and ideal for plant growth.

Sandy Coastal Soils: Light, draining soils along Bellarine and Gippsland coasts.

Clay Loams (River Valleys): Found along the Barwon, Goulburn, and Murray rivers — nutrient-rich from ancient flooding.

Granitic and Stony Soils: Thin, gravelly soils of the You Yangs and central uplands, supporting hardy grasses and shrubs.

Each soil reflects its geological origin — volcanic, marine, or sedimentary — and carries ecological and cultural meaning.

The Colour of Country

To Indigenous peoples, soil colour represents both physical and spiritual qualities:

Red ochre symbolises blood, law, and ceremony.

White and yellow clays are used for painting and healing.

Black soils of volcanic plains represent fertility and fire.

These colours tell stories about the land’s origins and serve as living links between geology and culture.

Wadawurrung Country: A Case Study Beneath the Plains

Wadawurrung Country — stretching from Ballarat to Geelong, the Bellarine Peninsula, and the Werribee Plains — is built on volcanic foundations. Beneath its surface lies a record of ancient eruptions, shifting seas, and sacred soil.

The Land Beneath

The basalt plains formed from lava flows around Mount Buninyong, Mount Elephant, and Anakie Hills, creating some of the youngest volcanic land in Australia (less than 2 million years old).

Beneath the basalt lies ancient sandstone and granite, remnants of the continent’s early formation.

Underground watercourses, fed by rainfall filtered through volcanic rock, sustain wetlands and aquifers.

Cultural Connections

For the Wadawurrung, these underground systems are alive with spirit.

Waterways running beneath the land are seen as veins of Country.

Caves and lava tubes are sacred sites — resting places of ancestors and stories of creation.

Ochre pits near Ballarat and Steiglitz were sources of sacred pigments, linking deep earth to ceremony and identity.

This understanding connects geological knowledge with cultural law — showing that the Earth beneath is not dead matter but a living being.

Stories of Earth and Creation

In many Victorian Indigenous traditions, the land beneath is shaped by ancestral beings:

Bunjil the Eagle, creator of the Kulin Nations, is said to have formed the hills, rivers, and plains of central Victoria, setting the laws that govern both people and nature.

Mindi the Serpent, associated with water and underground movement, embodies the unseen power of the Earth — its flowing energy beneath the surface.

In some stories, the tremors and rumbles of the ground are the stirrings of these ancient spirits, reminding people to live in balance with Country.

Across Australia, these stories mirror geological events — such as volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and rising springs — encoded in oral histories thousands of years old.

Australia-Wide and Global Context

Australia’s underground landscape is as diverse as its surface.

Northern Territory: The sandstone escarpments of Arnhem Land hold ancient cave systems filled with freshwater springs.

Western Australia: The Pilbara’s iron-rich rocks are among the oldest exposed on Earth, over 3.5 billion years old.

Tasmania: Caves and karst systems, like those at Mole Creek, formed through limestone dissolution and feature in palawa stories of water spirits and transformation.

Global Analogies

Māori (Aotearoa): Speak of Papatūānuku, the Earth Mother, whose layers and roots sustain all life.

Native American Nations: View the underworld as the realm of ancestors and renewal.

Andean Peoples (South America): Honour Pachamama — the living Earth — whose soils and mountains are sacred providers.

African (Yoruba and Zulu): Recognise sacred mountains and earth as the womb of creation.

Across cultures, the ground beneath is both physical and spiritual — a foundation of identity and connection to the cosmos.

The Science and Spirit of What Lies Beneath

Modern science and Indigenous knowledge both recognise the Earth as dynamic and interconnected:

Plate tectonics shows that continents drift and collide, shaping landscapes over eons.

Volcanism and erosion recycle the crust, forming new soils and mountains.

Indigenous ecological law teaches that Country breathes and renews itself through cycles of fire, water, and earth.

In both views, the land is not static but alive — constantly changing, yet eternally present.

Colonisation and Change

Colonisation disrupted Indigenous relationships with land and soil.

Mining and quarrying damaged sacred ochre pits and caves.

Farming practices eroded volcanic soils, altering natural fertility.

Western maps and property laws redefined Country as commodity, not kin.

Yet Indigenous communities today are restoring these connections through cultural mapping, environmental restoration, and truth-telling about the land’s deep time history.

Revival and Learning Today

Across Victoria, programs by Traditional Owner groups, universities, and museums are reconnecting science and story:

Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation teaches the geology of Country alongside Dreaming stories.

Budj Bim combines volcanic science and Indigenous aquaculture engineering in educational programs.

Geoscience Victoria collaborates with communities to record cultural and geological histories of volcanic plains and soils.

This integration of disciplines reveals that caring for land begins with understanding what lies beneath — both materially and spiritually.

Conclusion

The land beneath Victoria holds stories older than mountains — written in basalt, ochre, and water. For the Wadawurrung and other Indigenous Nations, these stories connect people to the Earth’s layers as living memory.

Science explains how pressure, heat, and time forged the crust and mantle; culture explains why this knowledge matters — to respect, protect, and sustain Country.

From the core’s molten heart to the soil underfoot, the Earth is both laboratory and law, ancient teacher and eternal ancestor. To walk on Country is to walk on the body of the world itself — a reminder that beneath every surface lies story, science, and spirit.

References

AIATSIS (2000). Settlement: A History of Australian Indigenous Housing and Culture. Canberra: AIATSIS.

Barwick, D. (1998). Rebellion at Coranderrk. Canberra: Aboriginal History Inc.

Broome, R. (2005). Aboriginal Victorians: A History Since 1800. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Clarke, I. D. (1990). Aboriginal Languages and Clans: An Historical Atlas of Western and Central Victoria, 1800–1900. Melbourne: Monash University.

Dawson, J. (1881). Australian Aborigines: The Languages and Customs of Several Tribes of Aborigines in the Western District of Victoria. Melbourne: George Robertson.

Gammage, B. (2011). The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Isaacs, J. (1987). Bush Food: Aboriginal Food and Herbal Medicine. Sydney: Weldons.

Joyce, E. B. (2010). Volcanoes in Victoria and the Western Victorian Volcanic Plains. Geological Society of Australia.

McNiven, I. & Bell, D. (2010). Fishers and Farmers: Historicising Aboriginal Aquaculture and Agriculture in Victoria. Aboriginal History Journal, 34.

Rose, D. B. (1996). Nourishing Terrains: Australian Aboriginal Views of Landscape and Wilderness. Canberra: Australian Heritage Commission.

UNESCO (2019). Budj Bim Cultural Landscape World Heritage Listing. Paris: UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

Written, Researched and Directed by James Vegter 16/09/2025

MLA

Sharing the truth of Indigenous and colonial history through film, education, land and community.

Copyright of MLA

Magic Lands Alliance acknowledge the Traditional Owners, Custodians, and First Nations communities across Australia and internationally. We honour their enduring connection to the sky, land, waters, language, and culture. We pay our respects to Elders past, present, and emerging, and to all First Peoples communities and language groups. This article draws only on publicly available information; many cultural practices remain the intellectual property of communities.